Summer, 2004.

I was staying in the Covent Garden section of London on someone else’s dime. A nice hotel in a nice part of town. Alfred Hitchcock grew up in Covent Garden. He filmed part of Frenzy there.

I had historical places to visit as well as things to do that were “of the moment.” I had been watching The Office (the original) and had it in my mind that I needed to track down Courage beer. I have no idea why I was fixated on this. I asked at every pub we went to. No one had it. I returned home a week later and found it half a block from my house. It did not live up to the mystery.

I spent most of the week at museums. I tried to gallery hop, but the only map I had was a Streetwise map. It was worthless in a city impossible to fully document on a pocket-sized laminated map. I read directions to galleries in a Time Out magazine and still could not find many.

The primary art goal of the visit was to see Hans Holbein’s The Ambassadors (1533) at the National Gallery. It is a mind-bender of a painting. It underwent conservation in the late 1990s. I taught this painting using slides that captured it before restoration. It was not the same. The conservation team has breathed new life into it. If you're unsure what you're looking at, I'll provide a brief overview. The figure on the left is Jean de Dinteville, the French ambassador to Henry VIII's court. The man on the right is Georges de Selve, a Catholic bishop. A few issues related to the Reformation are illustrated in this piece. First, there is a Catholic bishop in the same painting with a book of Martin Luther’s hymns. A broken lute string is meant to represent a spiritual discord at work.

A more comprehensive view of the work is revealed in the arrangement of objects within the painting. A crucifix hangs in the top left corner of the painting. The top shelf contains astronomical tools of the era. The second shelf contains objects of earthly pursuit - math, music, and a geographically impossible globe. The bottom contains a skull, stretched anamorphically in space, at odds with its surroundings, as if it were from another dimension. The painting has been conserved on several occasions since 1533. At one point, a conservator must have been so confused by Holbein’s realism that he painted the curtain over the crucifix, hiding it for years. This disrupted the hierarchy of the painting, from top to bottom: heaven, the cosmos, Earth, and death. Heaven sits in the same reality as the cosmos or Earth. It is death that sits uncomfortably in the space. Holbein reinforces that in The Ambassadors. Death is unnatural compared to the rest of time and space. To paraphrase George MacDonald, “You don’t have a soul. You are a soul. You have a body.”

Seeing this painting is a remarkable experience. I sat on the bench in front of it for a very long time, watching people walk up to the right side so they could see the skull snap into its correct shape when viewed from the proper angle. Over the past 20 years, I have known several people who have visited London. I always say, “Go see The Ambassadors.” No one has taken my advice so far.

Flash forward to the winter of 2014. Birmingham, AL. Upon moving back to Nashville, my family would take trips to the region's art museums. With no major collecting museum in Nashville, I wanted to survey the art I could draw inspiration from. After 14 years in Philly, I had come to lean on the Philadelphia Museum of Art as a place to solve a problem I was having in the studio.

I was familiar with the Knoxville Museum of Art from my time in school. We visited the Hunter in Chattanooga, the Memphis Brooks, the High in Atlanta, and the Birmingham Museum. The BMA was hosting a Delacroix show at the time, which seemed as good a reason for a day trip as any other.

The Delacroix show was good, but the highlight was seeing Kerry James Marshall’s School of Beauty, School of Culture (2012). The painting is often described as “the one that borrows Holbein’s skull.” Instead of anamorphically situating a skull in space to show how death is at odds with our reality, Marshall stretches Disney’s Sleeping Beauty in the space of a Black beauty salon. Greek beauty standards are not welcome at this establishment. We have our own thing going on, thank you very much. The discussion of Holbein’s influence seems to end with the skull, but note that the walls and floors are saturated versions of Holbein’s space. In the spirit of our remix culture, Marshall juxtaposes other references, celebrating art like Lauryn Hill’s debut or a Chris Ofili show at the Tate. There are also references to Velázquez and Rembrandt tucked away. This is not a rejection of Western art. Marshall is a student of it. As an attentive student, he noted what was missing and has used his career to fill in deliberate omissions. To quote A Tribe Called Quest, “We Got It from Here... Thank You 4 Your Service.” I don’t know how other people feel about American art this century, but it was hard for me to walk away from this painting without thinking I had just seen the best American painting of the new century. I feel the same way over a decade later.

Back to London.

This set of posts aims to document what I consider the beauty of the century. Two more highlights from that trip stand out to me, one contemporary, the other not so much.

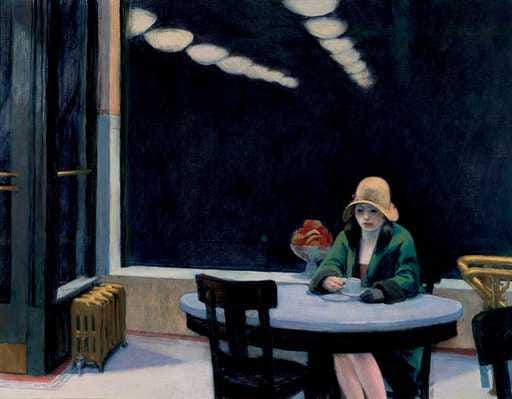

I won't say too much about this, but the Edward Hopper retrospective at the Tate Modern was one of the most tastefully installed shows I've seen at a museum. Hopper’s work is about isolation. The installation reinforced that by keeping the paintings far apart from one another. With rare exception, figures never interact in a Hopper painting. The Tate was not going to allow one painting to speak to another.

The contemporary jewel of the week was Tom Friedman at the South London Gallery. Friedman was (and I assume still is) recognized at the time, along with similar artists such as Tim Hawkinson, for their ability to reinvent the ordinary. Friedman straddles the conceptual and the formal, reconsidering mundane materials with accomplished craftsmanship.

Beyond the art experience, I struck up a conversation with a guy who appeared to be my age while on the bus back to Elephant and Castle. He off-handedly mentioned liking the new Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds record, the double album, Abattoir Blues/Lyre of Orpheus. I had not thought much about Nick Cave in about 10 years, but this encounter persuaded me to give the album a chance. Twenty years and hundreds of dollars later, my record collection is filled with Cave’s music, and I have seen either the Bad Seeds or Grinderman in concert four times. Thanks, British postman, whom I will never meet again.

Abattoir Blues starts with “Get Ready for Love.” It blasts out of the speakers similarly to Shelby Lynne’s “Your Lies.” Drums and guitars pound, and I once again found myself thinking, what can follow these first few seconds? Cave’s answer is to scream, “Get ready for love! Praise Him!” like it’s a threat.

Similar to Holbein finding Heaven a reality and Death at odds with it, Cave reflects The Ambassadors hierarchy in “Hiding All Away”:

“Some of us we hide away

Some of us we don't

Some will live to love another day

And some of us won't

But we all know there is a law

And that law, it is love

And we all know there is a war coming

Coming from above

There is a war coming”

Twenty years later, a more mature Cave would find a different way to express a similar thought on “Wild God.” Less of a warning and more of a plea:

“Bring your spirit down”

I can’t keep everything arranged in a tidy way, so I will conclude this with two movies and a book related to the Aughts, and finish with a triumphant moment in sports that occurred a year after my trip to London.

The Looming Tower is, unfortunately, a great book. Lawrence Wright’s history of al-Qaeda, Islamic fundamentalism, and the success of 9/11 is a challenging but necessary read. I had the common sense to read it at home, as opposed to The 9/11 Commission Report, which I read on the plane on the way to London. The woman next to me did not like that. I don’t know what I was thinking. It had been released two weeks earlier. It was the book I was reading.

Wright’s narrative of the rise of al-Qaeda is a maddening account of how many times al-Qaeda could have failed. I would sometimes forget what book I was reading and think, “Oh man, we’re going to get them now.”

Did we learn anything from it? Nope. A little more than a decade later, elected officials would refer to ISIS as a “JV team.” We still underestimate the people out to harm us.

Errol Morris has made a career out of getting people to talk. With The Thin Blue Line, he helped free a man who was wrongfully convicted from jail. He is a documentarian of legendary status. It is a sad reflection of the values of our culture that his body of work has not been rewarding enough to keep him from having to do Chipotle commercials. I don’t blame him. I blame the rest of us.

In a ten-year period, Morris convinced two former Secretaries of Defense to sit down for hours of interviews to discuss the impact of war. With The Fog of War, he interviewed Robert McNamara, allowing him to do the same thing Morris allows everyone to do: fill the silence. McNamara’s tone is somewhere between defensive and “If everyone would just do what I want do…” But at least he could admit when he misjudged his enemy. It is important to remember that McNamara is being interviewed nearly 40 years after the events he was discussing. He was in his mid-80s and had the benefit of revelation through the passage of time and very little to lose.

The math on The Unknown Known is different. Donald Rumsfeld was also in his 80s, but less than 10 years removed from his actions. He was still not ready to give up what McNamara could (not that McNamara gives up much).

Both movies are important historical documents and a window into the actions of those in power.

For something lighter, here is a sports highlight for the century. When I created the list, I aimed to include only sports moments I witnessed firsthand as they unfolded. Except for two or three, that is true.

No tournament defines American golf more than The Masters. No American golfer has defined this century more than Tiger Woods. It is impossible to determine what his greatest shot has been, but his most iconic is probably the chip-in on the 16th hole during the final round of the 2005 Masters. The ball’s pause at the lip of the cup is gravy, and I’m sure the executives at Nike were grateful as well.