Things I learned the easy way at horse camp: 1. How to clean stalls. 2. How to brush and groom horses. 3. How to pick out and clean their hooves. 4. How to feed them. 5. How to ride them.

Things I learned the hard way at horse camp: 1. Do not touch an electric fence. 2. Do not try to steal anything from a vending machine because the owner might see you do it and slap you silly. 3. Do not throw a ton of hay down the chutes that lead to the horse stalls for the same reason that you do not steal from a vending machine. 4. Do not double up on a pony ride with your friend if the pony has recently given birth. When that pony knows she is going back to the barn, back to her colt, she will take off at a ridiculous speed and buck you off to lighten her load. If you are lucky, you will not get stomped by the pony once you are on the ground.

My lone horse camp experience occurred when I was six or seven. It would be disingenuous to say that I attended. That would imply intent. I had a friend who owned a pony. He went to a camp where his family stabled his pony and invited me to go with him. If you ever know anyone who owns a horse, it is probably just one kid from your childhood. It is not a gang. If you know more than one person who owns a horse, you probably also own one. You are horse people. From a 6–7-year-old's perspective, this boy's family seemed to do well. Their garage was so big that he had a basketball goal installed inside. That blew my mind. It still blows my mind. He had a go-kart and a zip line in his backyard. We took his go-kart through the woods in his backyard, and a large tree branch fell from a tree just as we passed under it. The branch fell on me, but not my friend. It was a million to one shot, but I was not going to find out if it was a million to two shot and never rode the go-kart again.

My memory of the camp is that it lasted all day. It seems like a lot for a kid with no farm experience to learn all this in a week. Maybe we were being used as free child labor. We cleaned stalls and horse hooves, along with other random chores. Someone who grew up on a farm might read this and laugh. "That's all you had to do?" No one over seven probably likes to clean horse stalls, but it was fun then. At some point, a person must lose their fondness for horse manure.

The week ended with a set of races. I was not remotely qualified for them. I might have been the only one at the camp who did not own a horse or a pony stabled at the farm, so I had about 4 hours of riding experience by the time they had us "race." I ended up in a contest where I had to carry an egg on a spoon while riding a horse. I could not walk and do that, much less ride a horse and do it. There were only two kids in the race: a girl named Julie and me. Julie could legitimately carry an egg on a spoon while sitting on a walking horse. I could manage no such thing. I made it two feet, and it fell. Someone picked up the egg and put it back on the spoon. It fell again…and again…and again. It would not break. Maybe they were hardboiled. It was muddy. Maybe that helped. There may have been some tears involved. Julie finished her race. The judge granted mercy and called the race based on my showing up. History records, I placed second, which is accurate but does not tell the whole story.

We spent the final night in a barn's hayloft. There was a nighttime horse ride. I do not remember much else, but that seems like a decent amount for first—or second-graders to experience in a one-week summer camp. I remember that my primary horse's name was Charlie. He was solid, but he decided to run rather than walk one day, which rattled me, and I had a meltdown. Charlie was dead to me after that.

That camp represents 90% of my total farm experience. Someone in Philadelphia once asked my wife why I did not have a country accent. She said, "Rob's southern. He's not country." True. Whether I lived in a small town or a suburb growing up, I was very much in a residential, "town" environment. Nobody ever had to get me up at the crack of dawn to feed anything. Laura Ingalls Wilder's family lived and worked on a farm. Nelly Oleson's family ran the mercantile. I am Nelly Oleson.

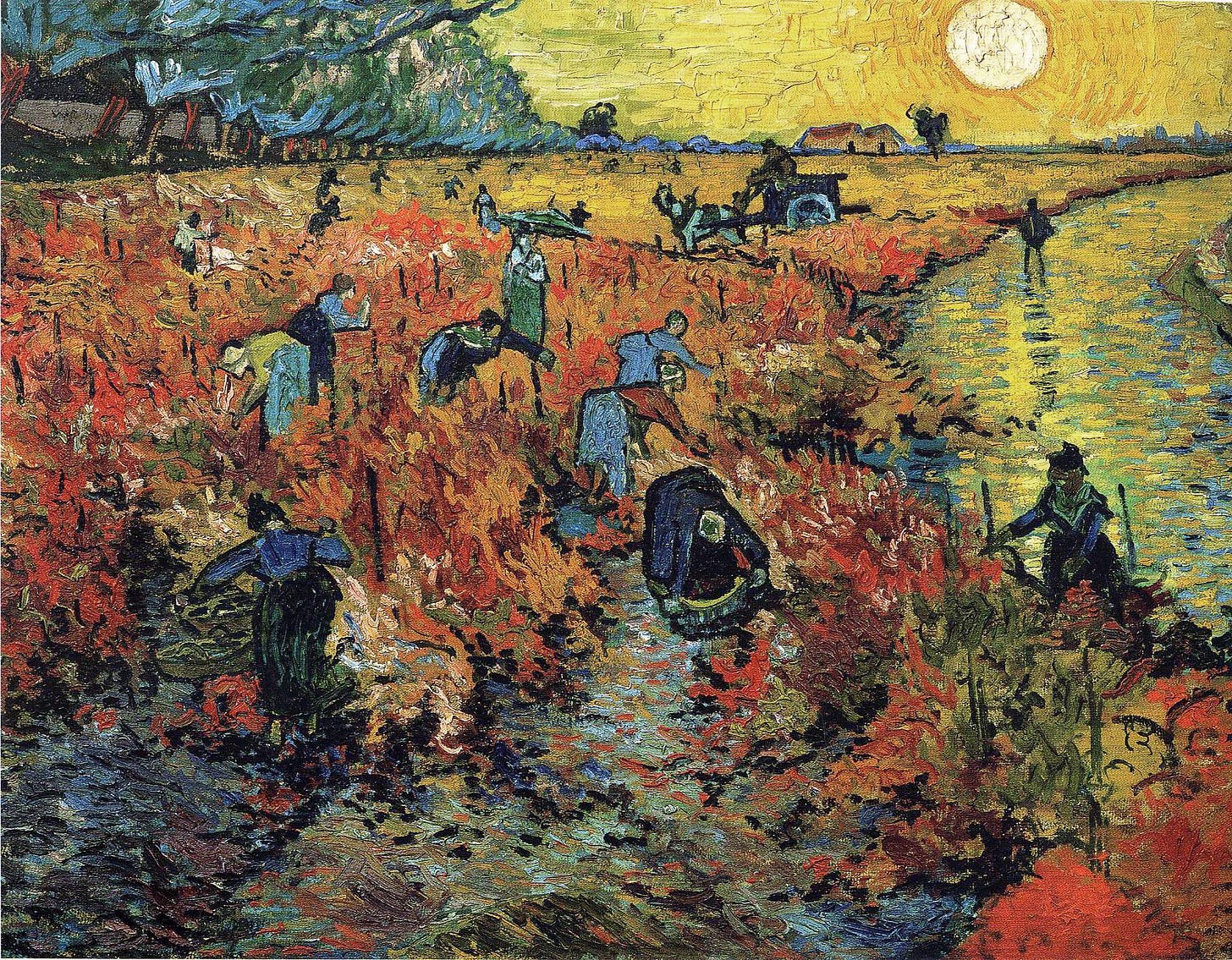

Despite that, or because of it, I do like northern European paintings that center on farm life. Historians refer to it as "peasant" life. This genre depicts these people's dignity, honor, and commitment to a simple life. Implied in this is a choice of a simple life. Like someone walked up to these people and said, "You can continue to labor in difficult circumstances and provide this country with sustenance and probably die early of some malady, or you can join us in the city during this continent's greatest economic boom. Poverty and farming it is? God bless you, noble peasant! Let me paint you." Despite being regarded as Realism, it is a Romanticism of a subject. The Realism extends only to depicting a “real” subject otherwise ignored by art history. These painters treated their subjects how U2’s Bono speaks about anything from Joey Ramone to Crest toothpaste.

A large number of Dutch and French painters committed themselves to this work. Vincent van Gogh considered himself one, as most of these painters were his true conceptual heroes. For the casual art fan, visualize what van Gogh painted in southern France, and you will see the connection. He was not a Parisian Impressionist painting the middle class engaged in leisurely activities and ridiculous amounts of bathing. He painted farmers. He was attracted to "sowers," "reapers," and "gleaners." It was all very Biblical for him. His formal execution differed radically, but his subjects reflected his Dutch predecessors.

The genre brought dignity to this slice of the Dutch population through artists' representations, but it was not like they could buy the art. Instead, the merchant class bought their pride. I assume the subjects appreciated the hat tip to their lifestyle, but I do not know how much they believed it. Very few people living this life would look at it and think, "You know, you're right. I'm a folk hero. Thanks for capturing that part of me." It would be like painting a version of that now, but the laborer in the painting would rather watch football than look at your picture. More than likely, they were glad to get paid to pose for the work. This is cultural history. This is recognition of a hard day’s physical work, which might be lacking in the life of the importer/exporter who bought it. I like this work either because of my limited farm experience or because I carry these same misguided stereotypes. My brief exposure or bias leads to a piece from the genre that sticks with me more than others.

17th-century Dutch painter Paulus Potter was 28 when he died of tuberculosis. His subjects were primarily animals, and, despite his premature death, Potter's paintings are judged to have influenced the way artists portray animals in Western art. Because of his early passing, he left behind a relatively small number of paintings and etchings, around 100. I would not want to be judged on 100 pieces if I died at 28. I am 50 and still would not want to be judged on my 100 most successful paintings.

Potter's focus was farm life: cows, horses, dogs, etc. There are a lot of low horizon lines to make the animals loom in monumentality. Despite his young age, he had developed a unique system of composition. He had one formula where the animal of choice was the most significant element- seemingly a horse, dog, or cow portrait. He had another method that focused on the landscape, with the animals clustered in the bottom corner. Potter had another compositional structure: a farm building or barn holding down one side of the piece and a door revealing part of the interior. The other side remained open in a landscape with a horse alongside the building and a smattering of farm animals in the foreground. He was masterful at foreshortening, which led to many cow and horse rumps in his work. He painted life-sized pieces and several intimately scaled works.

I am most familiar with Potter's Figures with Horses by a Stable from 1647. It is small, about 18x15", and has one of those titles that a curator at a museum slaps on it when it enters a collection. Potter was around 21 when he made it. It falls under the "barn on one side, infinite landscape with a horse on the other, animals in the foreground" method. It hangs at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, as do most pieces I know better than others. Some of my coworkers and I were confused by this piece for a long time. We were confused about what the farmer was doing to the horse. It ends up that he is probably brushing it. The horse's body blocks your view of the farmer's hands, so that mystery sat with us for a few months. You see the farmer's glowing face. When you get too close to the painting and look at the farmer, you forget where the light illuminating his face is coming from, and you can fool yourself into thinking that the light is coming out of the horse’s butt in a mysteriously veiled way like the briefcase in Pulp Fiction. I will say that I learned enough at horse camp to know that the farmer is standing in the wrong spot. Standing directly behind the horse, he is just asking to get kicked in the stomach. I took a hoof to the butt during my week because I lost focus for a bit.

The look of pleasure on the farmer's face is odd, considering that he is staring at a horse's rear end lit by an invisible light source that one can only assume is a window or open door in the barn out of frame to the right. It is an intense light compared to the limited value range in the background and the cloud. The closest cow to the fence line has a shadow in line with what could be lighting up the horse and farmer, but it is the only animal that registers a shadow. It seems like the sun is low, which makes for some confusing light because if it were that low, would it be that white? It is the beauty of art, I suppose. Lie, to tell the truth, or bend elements and principles to get your desired image. It is like in The Big Lebowski. The Coen brothers tried several takes to throw a bag of underwear ("the ringer") out of a car and over a bridge. They could not get the arc of the bag's flight to be what they had envisioned. It takes great strength to throw a bag out of the car that high in the air, especially while rolling. After a few failed attempts, someone suggested driving the car backward and throwing the ringer at the car, reversing the film’s direction in post-production. As with everything else about The Big Lebowski, it works. (1)

Potter bends the rules to make it work. He beats Magritte to his Empire of Light trick by 300 years. There are issues. Despite Potter's gift for foreshortening, the white horse's head does not jive with the body. A stall trough blocks the point of connection of the neck to the body. It covers where an unsuccessful meeting takes place. Something is amiss. If I had to guess, the horse's body was from one sketch, and the head was from another. Potter stitched them together with enough success. The horse outside the barn with the two figures is exquisite. It is a beautiful positive shape, cutting a high contrast with the ground. You could remove that shape and make an early 20th-century modernist abstraction. It would sing.

The rest of the foreground is an arrangement of chickens and twigs to activate the lower fifth of the piece. I looked at this a lot when I had an exhibition of landscape drawings a few years ago. I would study this and Dürer to see how to activate the ground. I needed to use beer cans and cats for props, but Potter seems to understand that you must put something there. Anything will do if it makes sense in the scene. For this, he has twigs on the left and chickens on the right. There is a dog outside the barn, scratching itself. Potter has invested significant effort in the dog's testicles. There is a pile of what I assume is dog feces next to the fence near the horse's back hoof. The boldest shot of color is in the nursing mother's dress. It calls attention to her but is also one of only a few solutions for not having her swallowed by the background. Her bonnet is abnormally lit, breaking another rule to ensure the piece's clarity and establish her presence. The tree growing next to the barn connects the barn, sky, and ground but seems poorly placed in a real-life situation. It would tear through that barn over the years. A cloud activates the top left, and Potter allows the top right to remain static aside from a couple of birds.

This painting became one of my favorites in the museum over the years because of the mixture of gentle rule-breaking, compositional prowess, and general oddness. I worked in this format in drawings for a while, giving me a few ideas. It was a structure that a friend lovingly referred to as "a tree, some people doing something and some crap on the ground." I was not trying to depict peasant life romantically, but I learned about representing landscapes. I always placed the horizon line higher than Potter because I was enamored with Düreresque overlooks into an infinite recession of space. However, I observed how powerful a subtle cloud could be and what elements I could alter to highlight an area yet still fit the intended vision. I am the furthest thing from an iconoclast. I am not a rebel. I firmly believe in tradition, but being an artist representing anything in a two-dimensional form means understanding that everything you put down on paper or canvas is abstract and, therefore, not true. Everything you make breaks the rules. Bending reality to your will is unavoidable, so do not get fussy about it. Say what you want to say and how it needs to be said.

The Coen brothers make/made great dramas and great comedies. They are starkly different from one another, and it is a remarkable breadth of talent. The Big Lebowski was released in 1998 and is now a streaming-era standard. It was their follow-up to Fargo, which was a return to the public discussion after years of less successful but compelling projects. Raising Arizona is a zany comedy that people connected with, but they followed it up with two difficult movies for the average viewer: Miller’s Crossing and Barton Fink. Fink swept the awards of the Cannes Film Festival: best picture, best director, best actor. Cannes changed the awards after that to prevent a single movie from winning all three again. John Turturro is incredible in it, as are John Goodman and John Mahoney.

Miller’s Crossing is my favorite Coen movie. The script is so precise, and the slang is almost impenetrable. It took me three viewings to figure out what was going on.

Fargo was an unexpected success and returned the Coens to the mainstream. It was a minimal noir movie that probably did not feel that different to them than the two that preceded it. But people liked the upper Midwest accents. Maybe they thought a good follow-up would be another zany comedy like Arizona, but Lebowski may have been too zany. It underperformed by comparison to Fargo. The follow-up to Lebowski, O Brother, Where Art Thou? would be equally wild and surreal, but it would do well. I am sure the Coens like to make successful movies to keep working, but trying to figure out what people want from them must be frustrating.