Fourth grade. I had a Nelsonic Pac-Man game watch that would unexpectedly explode in digital noise during the middle of class, even if I was not touching it. My teacher never believed that these beeps and blasts of the soundtrack were unprompted. How could the fine craftsmen at Nelsonic produce such a glitchy product? A good carpenter does not blame his tools, my friend. After some time, I left the watch at home. The direction buttons stopped working shortly after that. The facing fell off and was lost. I never replaced the battery once it died.

My fourth-grade teacher was relatively young, in her 30s, but she appeared older. My memory is that all my elementary school teachers looked like they were ready to retire, but I bet most of them were not even 35 years old. Her hair had a fixed styling that a grandmother would get when someone took her to the beauty parlor. A "washed and set" weekly appearance. She wore a lot of long cardigans that made her look smaller and older than she was. She also had a burned-out demeanor and coffee habit that finished the whole package. I once walked up to her desk to ask her a question. She sat, hunched over paperwork, writing. She did not look up from what she was doing or allow me to say a word, nor did she offer any comments herself. While still walking towards her, she put her left elbow up on the desk, extended her index finger upwards to stifle any sound I might make, and then shooed me away with her hand with a motion that suggested I should turn around and go back to my desk. If I had a pencil stuck in my eye, she never would have noticed.

A friend of mine had a nervous habit of flopping his feet back and forth under his desk while working on math or something else requiring concentration. Today, he would have a fidget spinner or whatever toy de jour is marketed for focus. His shoes occasionally hit the floor under his desk, making a squeaking sound. It was noticeable but not annoying to the average 9–10-year-old classmate. The squeaks did not sit well with our teacher. She issued a warning. My friend tried to stop, but kids are kids. Ten minutes later, a squeak squeaked. Punishment was quick and straightforward: stand in the hall and make your shoes squeak for twenty minutes. Twenty solid minutes. The principal walked by mid-punishment and asked what my friend was doing. He was ten years old, so he gave the most basic answer because most 10-year-old boys are not yet gifted in the oral tradition of storytelling. “I’m making my shoes squeak.” I can only imagine the confusion in the principal’s mind, but her response was, “Well, stop it. It's annoying," and she walked off. Sound stopped coming from the hall. My teacher walked out and, without asking a question, said, "I don't hear squeaking. I want to hear squeaks," and closed the door. My friend started up again. The principal returned. A discussion ensued between the teacher and the principal. The principal granted parole to my friend.

For Halloween, we carved pumpkins in art class. I do not know who thought it was a good idea to give 25 kids small pumpkins and sharp knives. The late 1970s and early 1980s must have been a time of thinning the herd. In first grade, we learned how to cross-stitch. That involved giving needles to 25 six- and seven-year-olds. The girl next to me managed to get her needle through the web of skin between her index finger and thumb on her left hand with no pain. She raised her hand to get the teacher's attention, but the needle and thread were connected to her, so when she raised her hand, she also raised the needle, the thread, and the embroidery hoop with her cross-stitched apple into the air with it. My fourth-grade class managed the pumpkin carving without impalement or bloodshed. The boy beside me brought in a motor, a red button, and a little wig. He carved a face into the pumpkin and a hole for the nose. He put the button in the hole, connected it to the motor inside the pumpkin, and put the wig on top. The wig lifted an inch when he pressed the button, spun around in a complete circle, and settled back onto the pumpkin. Needless to say, that boy is now an engineer. (1)

The most significant event of fourth grade was getting glasses. I began the school year in the back of the class. I started failing math. I explained this by saying that I could not see the chalkboard. My teacher moved me to the front of the room, six feet from the board. I still could not see the board. I was outfitted with large, brown plastic frames that swallowed my entire face.

Our local optometrist was a stickler for the rules of vision. He wore large frames and was very persuasive in convincing parents to do the same thing for their children. The only other thing I remember about him is that his daughter was the girl in my sixth-grade class who spent all day crying when Andy Taylor and Roger Taylor left Duran Duran.

"Your eye must be in the center of the lens." And apparently, the overall lens must start above your eyebrow and finish at your cheekbone. This goggle-style was set in place and would determine my undateable appearance for the next nine years, until my glasses were knocked from my head when a mosh pit spontaneously formed around me at a club during my freshman year of college. One hundred students trampled my glass while responding to the local goth/Joy Division band.

Once I started wearing glasses, the other students reduced my social status to one step above Darryl, the kid who kept a booger collection in his desk. My teacher moved me to the middle of my row of desks. There is a part of driver's education where they teach you how to drive safely on the interstate. The rule is that you always need a safe direction you can go. Slamming on your brakes to avoid something in front of you or beside you is not an option. It would be best if you were in a position to accelerate ahead or move to the side. Do not travel at high speeds with someone in front, behind, and on either side of you.

The same applies to your seating location in elementary school. When I was at the back of the class, I had an exit behind me. When I was blind, and in the front, no one was in front of me. Now, in the middle, there was no escape from the social order of fourth grade. I sat behind a popular girl/future cheerleader. A new girl sat to my right. She had joined the class halfway through the fall semester. She looked older than us because she had braces. I was slow to understand what was happening, so when she came into the class for the first day, I thought she was a fifth-grader delivering a message to our teacher. She had a habit of squinting in deep thought while putting her tongue between her molars and slowly chewing on it, which struck me as "older" behavior. It was probably a response to anxiety. It made her look more mature, but no, she was just new. Unlike me, her social standing transferred across state lines. She benefited from moving to the same street as the popular girl in front of me. Location. Location. Location.

Notes were passed. I was not privy to any of the contents. I most assuredly was not part of the contents unless they made fun of my glasses. The new girl had "I (heart) Kevin Bacon" written in ballpoint pen on a fabric-bound three-ring binder.

“Is he in fifth grade?” I asked.

“Who?” replied the tongue chewer.

“Kevin Bacon.”

“Oh my gosh.”

“What?”

“You don’t know who Kevin Bacon is?!”

“No.”

Eyes roll.

“He’s in Footloose. OK?”

I imagine this from the girl's perspective. My grossly magnified eyes were addressing her from behind my glasses, while my Pac-Man watch was probably making a beeping noise. The derision and exhaustion in her response were not without provocation.

What’s a Footloose? I did not say that. I knew the titular song, "Let's Hear It for the Boy," "Holding Out for a Hero," and "Almost Paradise." If you told me that all those songs were coming from a single movie soundtrack from a movie that I had never heard of, the world would have snapped into focus around me. I spent the rest of the day without asking questions and went home, confident that Kevin Bacon had sung the song "Footloose." (2)

The separate acts of looking and seeing were reborn in me with glasses. I had been in school for over four years before I had a problem seeing the board. Whatever changes affected my vision were immediate. The first fitting of my glasses happened at a building adjacent to the Hendersonville hospital. It was a building separate from the hospital itself, but overlooked the helicopter landing pad. I looked out the window and saw a blurry gray area. Someone put glasses on me while I was looking outside, and I saw a helicopter 100 feet away. It was not there, and then it was there. Yes, I needed glasses. A person should know if they are within 100 feet of a helicopter.

Eyeglasses restored my ability to function physically in the world. My grades went back up. I got my shot back in basketball, even if I was constantly worried about my glasses getting knocked off my head. My ability to emotionally engage in the world became more difficult. Kids are kids, and kids sniff out weakness. The friend of mine who has had glasses since school began? He was fine. His hardware was part of the package. My glasses? They were new. Something happened to me. Kids sensed a diminishment in my being. I was less than what I was, and now, thanks to the persuasive stickler for the rules that was my optometrist, I looked odd.

There was a mix of frustration and gratitude in me with glasses. I could see, but at what cost? I grew in appreciation. I am reminded of it each semester when I teach Flemish primitive painting and point out people holding eyeglasses in their hands in paintings from the 1430s. In Jan van Eyck’s Virgin and Child with Canon van der Paele, van der Paele is depicted kneeling, holding a book and a pair of glasses. They seem so prominently displayed not only to show that he is a learned and well-read man, but that he had the tools to be such a person. His options would have been far more limited if he had been born 100 years prior.

The St. John’s Hospital museum in Bruges houses a painting by an unknown artist, a portrait of Franciscus de Wulf. De Wulf was known for his treatment of cataracts. The picture depicts him standing with a child in front of him. The child's right hand holds de Wulf's side. The child's head is turned towards the front of the painting, looking at us. De Wulf's left hand cups the head, so all that is visible of the child is their left eye. De Wulf's right hand hovers above the child's face, his ring finger and pinky resting on the left temple for steadying. His remaining fingers hold a scalpel, the tip of which is either resting on or is barely perched above the white of the child's eye. My "bigger is better" optometrist seemed less cruel. What would life have been like for me 700 years ago? I could not see a helicopter that was 100 feet away from me. I would have walked off the edge of a cliff before the invention of glasses.

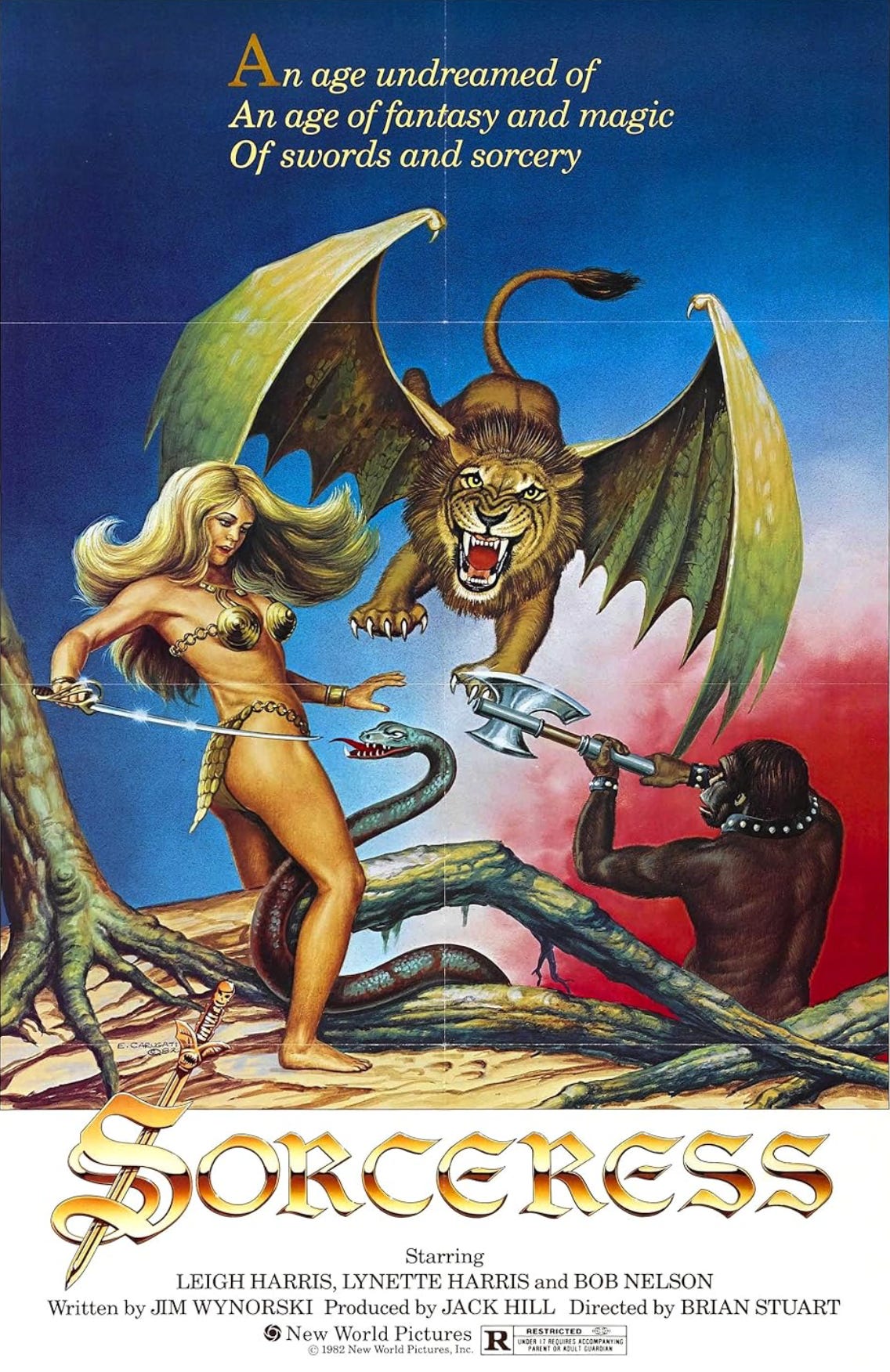

Later that year, I turned ten and started fifth grade. I finally had friends outside of my neighborhood, so I had places to go and people to see. There were occasional sleepovers. My friend, Chris, convinced his dad to rent the 1982 fantasy movie, Sorceress. I knew nothing about nothing, but I could still look at the box for this video and think, “This is not going to last long.” His father did not see the movie box. Chris just handed him the case with the video in it. The label read “Sorceress.” Missing from the father’s context was the box with the blonde woman in a gold bikini, with a sword, fighting a snake while a monkey wearing a spiked collar wielded an ax against a flying lion. There is no flying lion in the movie. The single blonde woman is really two blonde women- sisters who were former Playboy playmates.

The movie opened with the violent death of a medieval mother of twin baby girls by what ended up being the girls’ father, a man named Traigon. He gouged her womb with a weapon that looked like a combination sword and rake. A mysterious wizard killed Traigon, saved the infants, and gave them to a peasant family to raise as boys to hide them from Traigon, who had been resurrected in a more potent form thanks to the dark arts. It is probably not too late for George Lucas to sue this film's production company. The next scene featured the two girls, now two adult women, skinny-dipping in a lake. At this point, Chris's mother started the timer in her mind. Chris probably started the timer as well. I do not think he anticipated his parents watching the movie with us. The women frolicked in the lake with Olympic-level stamina until they realized that a satyr was observing them. They commented on the "horn" between his legs. "How does he play it?" Eventually, the women (who were raised to believe they were men) emerged from the water, fully exposed, and pummeled the satyr. "Nope!" Chris's mom yelled out. Chris laughed and then protested as she turned off the movie. He knew it was a long shot, but you miss every shot that you do not take. That was the end of Sorceress and probably the last time Chris's mother put his father in charge of going to the video store. For this brief moment in time, I knew more about Sorceress than I did about Footloose.

The following day, we ran through the den where his mother sat, watching Rear Window. I recognized Jimmy Stewart, so I sat down to watch. Jimmy Stewart, I knew. Raymond Burr, I knew from Perry Mason. Kevin Bacon? Was he in fifth grade? I was not familiar with Grace Kelly, but she seemed to command the screen more than the two ladies from Sorceress. My “I like girls” moment could be pinpointed to Grace Kelly’s screen arrival in Rear Window, which, if you think about it, is downright wholesome as far as sexual awakenings go. The Sorceress women did not have much effect on me.

To a patient 10-year-old, Rear Window is an interesting puzzle. Did Lars Thorwald kill his wife, or does L.B. Jefferies imagine things after weeks of being stuck in his apartment during a heatwave? Chris did not want to watch Rear Window, but I ignored him. His mom and I finished it.

After that, it felt like Rear Window was always on television. It had been re-released in theaters in 1983 and became a TV staple after that. It was broadcast on either TBS or WGN every month for the next five years. I watched it every time it aired. A Suncoast Motion Picture Company video store opened in the local mall during my freshman year of high school. I bought a copy of the movie and might have watched it once a week for the next three years. Since then, I have seen it three times in the movie theater. If it is playing and I am available, I will be there. (3)

Glasses helped me look. Rear Window helped me see. It is a two-hour murder mystery, but that serves as an entertaining structure for an artist to demonstrate what it means to observe and construct patiently. Competing potential futures are presented to the protagonist as vignettes unfolding in separate apartments that he follows from across the courtyard. Symbolic objects carry varying interpretations depending on their position in the plot and the perspective of the observer. The camera stays in the protagonist's apartment, aside from a handful of quick shots that Hitchcock should have removed from the movie. It is his version of events. It is his construction. Is this receptive or projective? A critic could argue for both. You are watching Jimmy Stewart try to prove that a murder took place. He is not even trying to solve it. He is trying to prove that it happened. But you are also watching Hitchcock tell you how to make art.

Your favorite movie of all time can be Star Wars. You must watch the sequels and the new series, dive into the mythology, read the books, read websites, and collect toys if the movie is to remain your favorite. You must embrace the movie and the franchise. There is a limit to what the singular, first movie itself can provide. It is not that the movie is not good, far from it. It just has a limitation built into it. The Empire must expand so that your appreciation can follow. If you can watch Rear Window as a 10-year-old, it can sustain your interest in a certain way. If you continue to watch it consistently for 30 years, it must grow as a work of art. There is no sequel, no mythology, no theme park, no streaming service. For it to remain engaging, dissecting it must continue to reveal its internal logic and layers of organization.

I recorded the full audio of the movie onto cassettes in high school and would listen to it without watching it. I had these tapes throughout graduate school. A faculty member entered my studio and heard a movie but could not see it. She said, "What are you listening to?" How do you explain that you are listening to a film you taped from your VCR without sounding a little touched? Listening to the movie reveals how much Hitchcock withholds from the script, how much he expects from the viewer, and how much he trusts them to follow along. So little of this movie is dialogue, which makes sense because Hitchcock started in the silent era. He knew that there was audio and visual and that seeing was paramount. If you are skilled as an artist, you can guide an audience through a story without explicitly explaining the narrative to them. A talented filmmaker shows the audience the story. It is disrespectful to the audience to tell them what they already see. Listening to the movie's audio reveals how much time passes between conversations, as well as how conversations often reveal aspects of the story that the audience could not see on screen, such as past events that influence the current dynamic of the cast. The rest of the audio consists of the score, ambient "city" sound, and the movie's long progression as a pianist writes a song —the second work of art being created as the movie unfolds. It serves as a guide to the artistic process contained within and developing a more significant piece of art.

Rear Window is a movie set in one apartment, overlooking the courtyard and the windows of other apartments that enclose it. The entire set consumed a soundstage. The studio floor was removed to use the basement as the courtyard. A drainage system was installed to prevent the stage from flooding during a rain scene. All lighting is mechanical and simulated. Aside from the film’s score and a poorly included helicopter shot, all sound, ambient or otherwise, is created on the set. It is as if Philip Seymour Hoffman’s character in Synecdoche, New York successfully controlled everything in his play. It is singular, Hitchcockian command, so it comes across as the best opportunity to see what he thought of making art. It is a series of organized set pieces. Any other apartment in the set could have been a separate stand-alone movie. (4)

I learned the value of limitations. The camera rarely leaves the apartment. There is no secondary location. No one needs to see Lisa Fremont's apartment or the police station. The story is in the apartment. Every solution lies in this room. I learned the symbolic value of objects, colors, and gestures before finding the Flemish primitives. I learned the importance of restraint, the respect to show for an audience, and, in relation, the expectations that you could demand from an audience. As media changed and expressions became more overt and direct, I saw that audiences have less required of them. The past fifty years of American art, music, and movies that broke into the larger national discussion became anchored in emotional resonance and not patient observation. The engagement between artist and audience was, in some ways, severed. Entertainment became an increasingly passive experience. The audience was expected to contribute nothing. All that was asked was to get swept up in the emotional current.

Now, people get mad if they do not understand a movie and are offended that they must watch it more than once to understand what is happening. Viewers and listeners have become less curious. Populist creators accept that passivity and meet their audience where they sit. If they think you are going to miss the point, they will grind the movie to a halt for an impassioned speech that operates as a thesis to the movie. If they cannot answer your questions in two and a half hours, they are more than happy to make a trilogy. If it does not seem like every character’s motivation and plot line cannot be thoroughly examined in a short amount of time, they will make you a streaming series. Frustrated artists do not want to answer every question the audience might have. They want to give their audience room to invent that which is not made known. They want to imply more than they want to declare and have a conversation with the audience. Now, some artists are hardening and withdrawing into something unknowable. Their audience is now each other. Few have found the sliver of space where creator and audience still communicate. The middle ground vanished.

What becomes of the artist who wants that to work in that middle ground? It appears that you can plod away in relative obscurity, but unless you have a populist mindset, you were going to toil away in near anonymity anyway. Hitchcock was smart. He could hide the football. He buried his art in engaging stories. He might have planted it too deeply in the story and, therefore, was not recognized for the skill that it possessed. He never won Best Director. He only directed one Best Picture, and it is not even his best picture. Only five of his movies won an Oscar of any kind. Rear Window received four Academy Award nominations. It did not win any of them. It lost the cinematography award to Three Coins in the Fountain. The Academy did not appreciate restraint and constant reinvention in a confined space compared to a Technicolor tour of Italy. It lost the screenplay award to The Country Girl. It lost the sound recording award to The Glenn Miller Story. Hitchcock lost the director award to Elia Kazan for On the Waterfront, which is justified. Hitchcock directed Jimmy Stewart, Grace Kelly, and Thelma Ritter. I doubt that was the directorial equivalent of herding cats. Kazan had his work cut out for him with the Waterfront cast.

If you seek this ever-narrowing sliver of middle ground, prepare not to win the golden statue. You might be mistaken for a populist, but never for an artist. They will dust you off before you die and hand you a gold watch for your service if you are fortunate. If your work is cared for after you are gone, a young artist might discover it and find hidden layers as they mature. And if your work is worth anything, that artist will never outgrow you and chase you for decades.

The same guy who made the rotating wig for his pumpkin in fourth grade made a human circulatory system for his science fair project in fifth grade. He cut a human torso out of foam board and covered it in clear plastic tubing. There was a mechanical pump where the heart should have been. It pumped a red liquid through the tubes and back into the heart. I tried to grow crystals, but I did not know how to do it. I asked a boy in my class because I knew he had done it. He had a minor speech impediment, so I did not understand him when he told me I needed alum. I do not remember what I thought he said, but whatever I bought did not grow crystals. Nothing grew. My science fair project was made at the last minute and was more of an illustration than a project. Afterward, the teacher read our grades aloud in class. She called students' names and asked if we wanted to know our grades. I said, "No." I still do not know what I got on that project.

Footloose was released in 1984. It starred a rising Kevin Bacon, Dianne Wiest, and John Lithgow. Between Footloose, The Lost Boys, and Edward Scissorhands, Dianne Wiest was a powerhouse in the "mom" role of the 1980s and 1990s, also turning in some great performances in three late 80s Woody Allen movies. She is consistently strong. John Lithgow is always impressive and has as much range as the Coen brothers. I hate to reduce anyone to a role, but no matter how bad the writing got on 3rd Rock from the Sun, Lithgow and the cast always managed to show up and make some of it work.

I did not see Footloose in its entirety until the pandemic. I had seen a lot of it, but only in bits and pieces. I also watched the 2011 remake. It is not that different, but it does one thing that the original did not, and as a result, it makes for a less impressive movie. In the original film, Ren (Kevin Bacon) must have a serious conversation with Reverend Shaw Moore (John Lithgow) to establish their relationship. The movie edits out the conversation. It probably was filmed, but there is more mystery in not showing it. There are only a handful of options for what they would have discussed, and it strengthens the movie to leave it unspoken to the audience. However, the 2011 movie uses the conversation, stating what the audience already knew, slowing the movie down, and potentially offending the audience's intelligence.

I have seen Rear Window over 200 times. That is not an exaggeration. When I became a teenager, I recognized that I was learning how to interpret visual language. It became a puzzle to piece together. There are probably more sophisticated versions of this. I would not have connected with them on a fundamental level regarding the plot and performances, and thus would not have reached the analytical stage. It was a gateway experience in the arts for me. Everyone who likes art needs art to meet them halfway until they are smart enough to handle more complex material.

Synecdoche New York is a 2008 movie written and directed by Charlie Kaufman. I do not remember much about it other than Philip Seymour Hoffman, who played a theater director who won the MacArthur Fellowship and turned a warehouse into a living theater. People could walk around and observe the play as if they were walking through a giant stage. It became an entire apartment building where different characters lived out their lives. The movie was somewhere between engaging and pretentious.